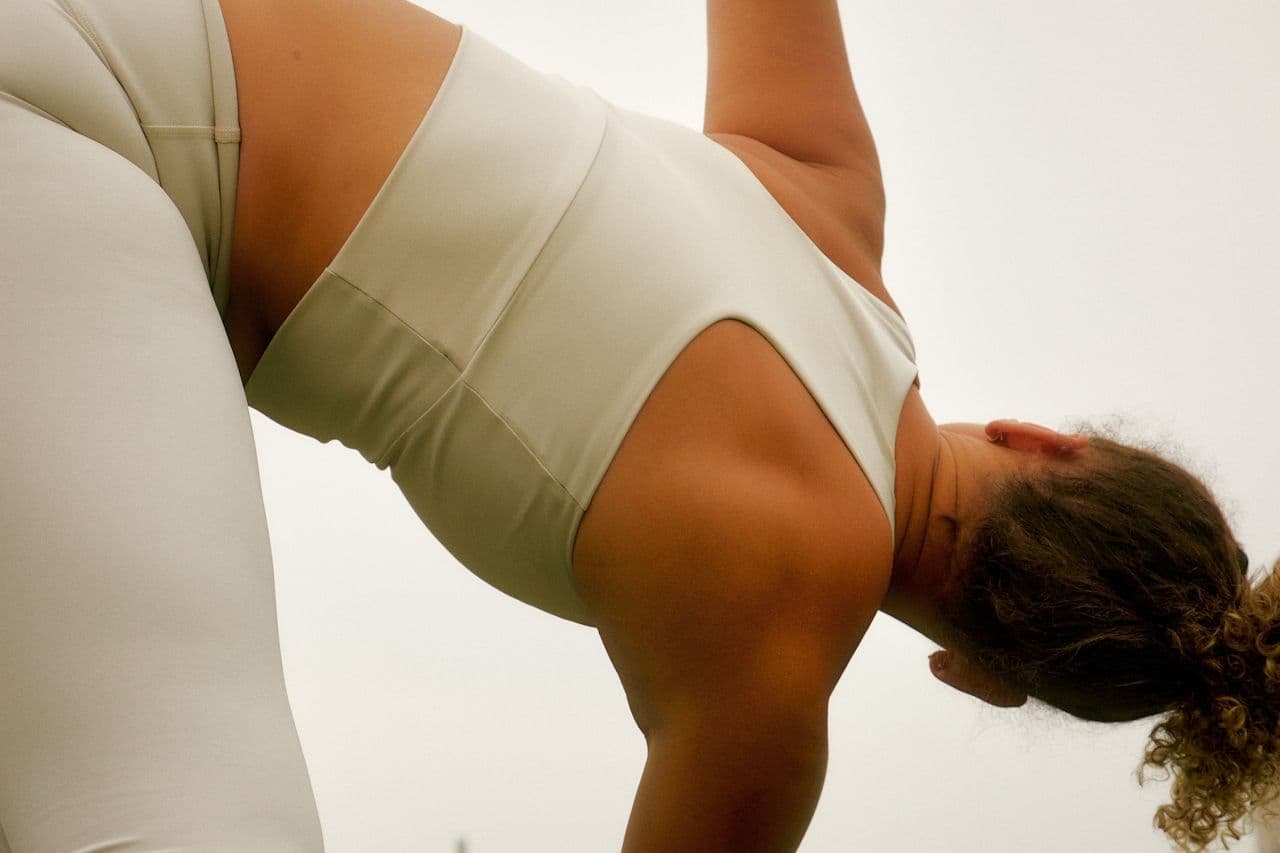

Jessica Scott

Jessica Scott is the Head of the Exercise Oncology Program and Principal Investigator at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

We know–there’s no way not to know–that exercise is paramount to staying healthy. Even though cancer changes so much about health, that part does remain true. Figuring out your new relationship to exercise, amid the chaotic frenzy of treatment and recovery, is not so intuitive.

Jessica Scott is the director of the exercise oncology program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; and before MSK, she worked at Johnson's Space Center, where they did exercise interventions in astronauts, and she brings a lot of these tools to shape how they deliver exercise training to patients with cancer. We spoke to her about fatigue, bone density, and her favorite recommendations.

Q:

What are some common physical effects from cancer treatment?

A:

We really think of cancer as these multiple hits, and there are three main factors that cause a lot of the side effects of cancer. So at diagnosis, a patient may have a preexisting condition, whether it's high blood pressure or some other cardiovascular conditions [that’s one hit]. They are then exposed to cancer treatment, and that can be everything from chemotherapy and radiation therapy, surgery, all of those direct hits to the body itself.

Third hits are kind of the consequences of the direct hit. When you're undergoing treatment, you don't feel great, so you become less active and you can either gain weight or lose weight. There are decreases in bone mineral density and muscle size and other things like peripheral neuropathy where you have changes in how you're sensing on your feet or your hands. Cancer-related fatigue is one of the major side effects that patients experience. There are things like brain fog, changes with your mental health compared to what it was before diagnosis.

Q:

We’ve heard from other experts that you just have to start moving, if it's a walk, if it's just sitting up in your bed, whatever it may be. How do you guide patients through the very beginning?

A:

I think it really depends on the level of activity that a patient is starting [from]. So, one of the first questions to ask is, ‘What is your current level of activity?’ If patients have not been doing a lot of activity over the past month, it is starting with small steps. Just doing even ten minutes a day of walking is beneficial, but the goal is to get up to two and a half hours of aerobic exercise per week–and get up to two days of strength training per week. That's what the current American College of Sports Medicine Guidelines recommend for patients with cancer.

Walking is one of the best forms of exercise, because it targets the heart, blood vessels, muscle, and bones, because you get some impact from walking, so walking is one of the best all round, whole body exercises.

Exercise is not one size fits all, and it's very individualized. Everyone has a different journey and a different place where they are starting, and that is a really important consideration when starting an exercise program. And it really depends on the type of cancer and the treatment that you've received, and that's why it's really important to check with your physician.

Q:

Obviously, it can be intimidating for someone who maybe didn't even do strength training before cancer to get started. How do you recommend people get started?

A:

We usually recommend starting with aerobic training first, and once you build up to getting 30 minutes, four or five times per week, then you can start adding in some strength training. This can start as simply as using body weight exercises, so you don't even need to start with any equipment if you've never done any strength training. [You can do] bodyweight squats or lunges, push-ups, or even wall push-ups. Once you've done several months of body weight exercises, then you can start to look into getting additional equipment, like resistance bands, or some light hand weights.

Q:

When you say aerobic exercise, if someone doesn’t really enjoy walking or running, what are some alternatives to that?

A:

If individuals do not like walking, there are other forms that are helpful for cardiovascular health, like cycling or swimming. Anything that gets your heart rate up and allows your breathing rate to increase.

Q:

Let's say you're talking to someone who feels stuck and they haven't really been moving at all during their treatment, but they really know that they should start. What advice would you give to them about just getting started?

A:

Checking with your doctor before you get started with a program is a good idea, especially if you're someone who's maybe at a little bit of a higher risk. If you've been treated with chemotherapy or targeted therapy, it's a good idea to go through some cardiovascular screening. There are cancer-specific gyms and specialists that are trained and working with individuals with cancer. The American College of Sports Medicine has exercise physiologists that are specifically trained to work with patients with cancer. There are certain programs like Livestrong at the YMCA where you can join a program with other patients. The American Cancer Society has guidelines outlined on how to get started and what goals, targets of exercise patients should go for each week, and those are all great resources to start with.

Q:

We know that a lot of women experience treatment-induced menopause from their cancer treatment. What are some of the physical side effects those women feel?

A:

With early menopause, there's the decrease in estrogen and that causes a lot of the symptoms and side effects that patients describe like, joint pain, muscle pain, weight gain, a lot of those side effects are related to that decrease in estrogen. A lot of women are worried about bone mineral density changes and some of those factors, and that's where it's very important to have an individualized exercise prescription. All of our programs are specific to a patient, looking at what their activity levels are, and how we can gradually increase their aerobic activity to get up to two and a half or even five hours per week of exercise. With the pelvic floor issues, physical therapists are really helpful in those specific targeted areas.

Q:

What about neuropathy? Are there any activities that can help mitigate those symptoms?

A:

There's not a lot of evidence on what can prevent neuropathy, but we think that exercise can help in mitigating some of those side effects or lowering some of those side effects. And there's different types of exercises that could be beneficial. For example, if patients are having a lot of neuropathy in their feet and walking is challenging, there's alternative exercises like yoga that are very helpful with balancing, which are some of the issues associated with neuropathy. That's where looking at some different modes of exercise is helpful.

Q:

You've had some very interesting diverse experiences from the space center before and now with cancer patients. Could you discuss what exactly makes working with people with cancer unique?

A:

It's so interesting to work in the field of oncology because there are so many side effects and so many different factors to consider. It's not like other chronic diseases where things build up gradually over time. With cancer, there is this one moment where they're receiving treatment, and it's a really big hit to the body. So we try to understand how we can prevent the declines that happen during treatment–and if declines happen during treatment, how can we reverse those declines and get individuals back up to where they were before treatment or even better than what they were above treatment. The goal is to get to a place where exercise is part of the standard of care for everyone that's been diagnosed with cancer.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.