Staying active is one of the best ways to combat the physical and mental side effects of cancer treatment. Research has found that exercise helps with many side-effects like fatigue and pain; it reduces feelings of anxiety and depression and helps with post-operative recovery; and it can also improve drug efficacy by enhancing blood flow through the body.

But we know (from experience) that there’s a lot standing in the way of your new exercise routine right now: you could be dealing with powerful treatments, long hospital stays, and busy schedules full of doctor’s appointments. And some days, your side effects may be running rampant and your energy levels are at an all-time low. You’re (very reasonably!) in no mood to do anything but lay on the couch.

This is the time to reimagine what being active means.

Physiatrist Dr. Sam Shahpar, who specializes in cancer rehabilitation at Northwestern Medicine, helps patients regain their strength and mobility during and after treatment. He says rehabilitation is an often overlooked part of cancer care and it’s important to ask your oncologist about it.

“I think a lot of times you don't even know that people are there to help you. I still get patients that come and see me say, ‘I wish I saw you three months before, a year before. I didn’t know that we can potentially address some of those things,’ and that ranges from basic activities of taking care of yourself and bathing and toileting to walking to exercise,” he says.

Some Common Physical Side Effects from Cancer Treatment

There are many side effects from cancer treatments that can impact your day-to-day physical activity.

Neuropathy, a common symptom from treatment, results from damage to nerves in parts of the body that can cause numbness, tingling, and pain, usually in your hands and feet. “It can cause problems with our fine motor [skills], so typing, buttoning, using anything that requires [the] skills of our hand[s]. It can affect balance, it can affect the ability to do certain activities,” Dr. Shahpar says. “Or people are just more careful, so [you] just stop doing those things if it hurts too much. Or [you’re] worried about [your] balance or ability, [so you] just don’t do them anymore.”

There can also be physical side effects from surgery and radiation depending on the part of the body that was affected. These can include radiation fibrosis, lymphedema, or other types of tightness and mobility difficulties post-treatment. Some of these conditions can also occur from the cancer itself. For example, fibrosis or tightness following breast cancer treatment may impact chest and arm mobility. Physical side effects due to treatment in the abdominal region can impact overall pelvic function, such as bowel, bladder, and sexual function; pelvic floor rehabilitation can help address some of these issues.

Cancer-induced fatigue is one of the most common side effects inhibiting movement. “It’s fatigue that is not relieved by rest,” Dr. Shahpar says. Exercise, he says, is one “of the best interventions that’s been shown” to address fatigue. It might sound counterintuitive, but even a short time period of gentle movement (like ten minutes) can counteract all the tiredness that makes you feel like you can’t possibly move at all.

What does being active during and after treatment look like?

The American Cancer Society’s guidelines recommend 2.5 to 5 hours of moderate intensity exercise or 75 minutes to 2.5 hours of vigorous intensity exercise, per week, for adults undergoing treatment, although going over those upper limits is ideal. However, experts say it’s important to adjust your activity based on how you are feeling, and to avoid comparing yourself to what you did before starting treatment.

Sometimes it’s easiest to start with stretching or gentle aerobic exercises like walking or jogging rather than jumping right into intense strength training or strenuous workouts. Always ask your care team what is safe for you to do.

“Even if it’s just a 20 minute walk a day, I've had people tell me how much that made such a difference for them and to make sure that I tell other people that,” says medical oncologist Dr. Alison Moskowitz, who works at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The American Cancer Society recommends scheduling walks with friends, playing active games with kids, joining a community sports team, or using a fitness app to track your progress. The American College of Sports Medicine has a survey tool that helps assess your current exercise levels and suggests exercise plans based on your side effects needs.

Colleen Sutphen, an oncology nurse, suggests a variety of gentle exercises if you’re having a hospital stay: “Whether it's just arm exercises in bed, whether it's sitting on the edge of the bed, whether it's just working in your room. You might not feel up to going for a walk in your hallway of the hospital that you're staying in, but just doing a little something each day. If you can go for those walks, go for those walks. It helps not just your mental clarity, but it’s going to help you keep up your stamina while you’re going through this treatment as well.”

Dr. Shahpar says that it is important to make movement less intimidating. If your movement has been really restricted due to treatment (like from a surgery), maybe you start by just sitting up for a bit when you wake up and during your meals, as it’s better for your digestion to be seated rather than laying down. Then, maybe you can try standing during TV commercial breaks or walking for two minutes and take a break.

But working out during cancer doesn’t need to be restricted to just walking and stretching. When done safely, strength training, more advanced cardio exercises, biking, group classes, competitive sports, dance, and other activities can provide more intense and varied options. As always, talk to your doctor about what activities are safe and effective for you.

Log your activity, for your team, but also for your own motivation

Experts say it’s also important to log your activity progress for both yourself and your medical team to gauge how you’re doing.

Jenna Benn Shersher, who was diagnosed with grey zone lymphoma when she was 29, kept a record of her progress as she trained for a half marathon during treatment. “It could be ‘I was able to get out of bed to go to the bathroom by myself. I was able to walk around the block. I was able to run a mile.’” Jenna pushed herself on the few days preceding the next round of her chemo throughout treatment.

“Every day that I felt like I could wiggle my toes when I woke up in the morning, that was usually how I would gauge what the day was going to be like. If it was difficult to wiggle my toes then I knew it was going to be challenging. If it was easy, then I knew that I was able to push myself a bit more, and so I started very slow,” she says. “In the beginning I was starting with the mile and then it was two miles and then it was three miles and sort of built incrementally on itself.”

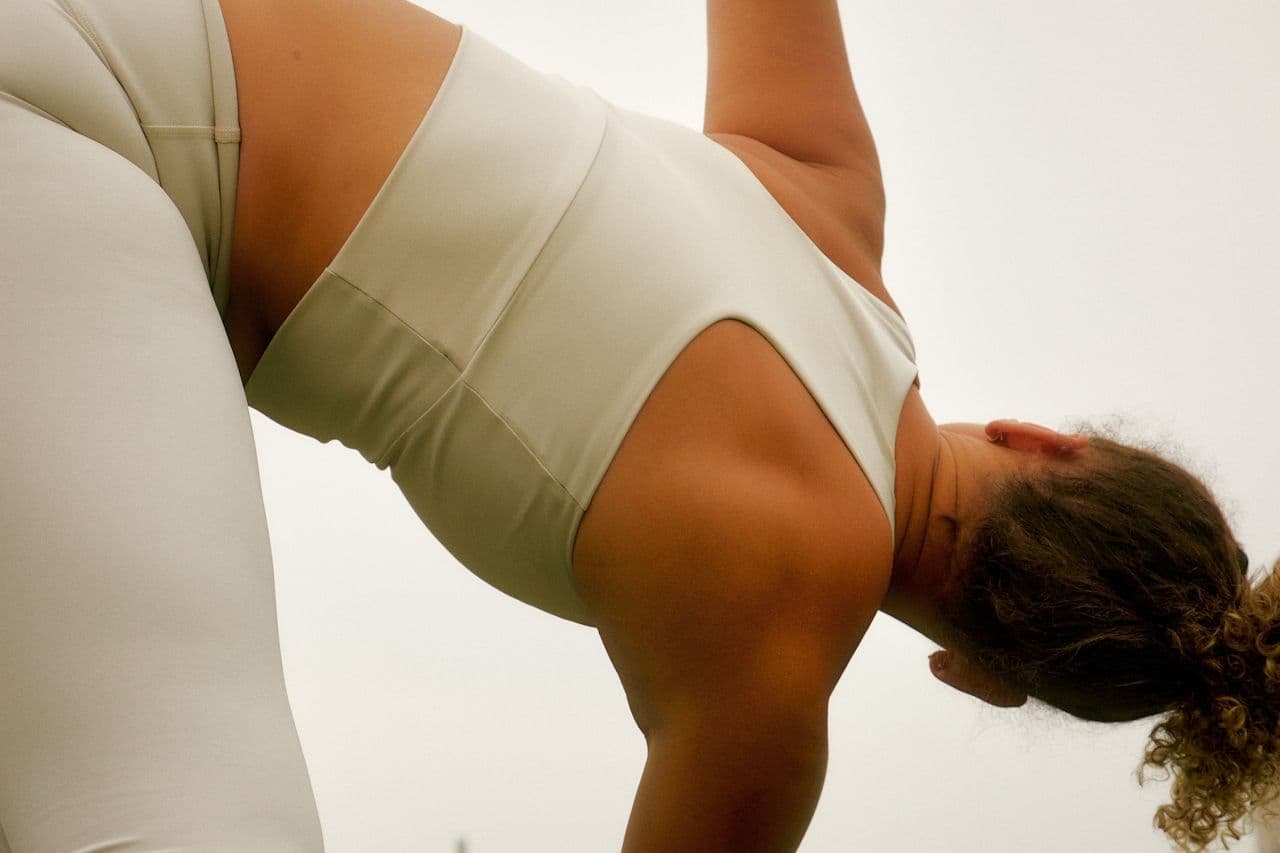

Staying active during treatment takes many forms and intensities, and it certainly doesn’t need to be running miles. Maybe it’s pilates, dance, or a sport you’ve loved since childhood or recently picked up – just make sure with your team that however you’re choosing to move your body is safe.

I’m ready to start exercising again. How do I start?

Just because you’re undergoing treatment doesn’t mean you need to put a full stop on movement. As long as it feels good for your body and your care team approves, exercise is key, and hopefully it can be something you look forward to and makes you feel strong. Jessica Scott, the head of the exercise oncology program at Memorial Sloan Kettering, says you should first start with aerobic training, even if it’s just 10 minutes of walking a day, taking the stairs, or parking further away from the grocery store. Then, as you work up to getting 30 minutes of aerobic exercise four to five times a week – hitting that 150 minute benchmark – you can integrate strength training.

“Strength training can start as simply as using body weight exercises, so you don’t even need to start with any equipment if you’ve never done any strength training,” Scott says. She recommends bodyweight squats, lunges, and knee- or wall-supported push-ups as good beginner exercises. As always, you should check with your care team about what activities are best for you.

Dr. Shahpar says that if you want to work with a professional physical therapist or physiatrist (doctors specializing in physical medicine and rehabilitation or PM&R), many insurance plans don’t require you to have your oncologist’s referral for you to go visit one. There are more restrictions for seeing an occupational therapist directly, but it is always best to check with your insurer and ask your oncologist if they have any suggestions for referrals first. But remember (unless your team has told you otherwise) there’s no need for this, there are plenty of things you can do on your own.

In addition to guidance from medical professionals, people have found motivation in team sports and group exercise classes, as they can offer a sense of community and support.

Executive director of Recovery on Water (a Chicago-based rowing team for breast cancer survivors) Tara Hoffman, was diagnosed with breast cancer when she was 43. She joined the team after recovering from surgery. This setting, she says, helps with accountability and empathy–and has given her a chance to make friends with people who are going through a similar experience.

“Our goal is to get women active again, making them feel that their whole life hasn’t changed,” Hoffman says. “They have the ability to be active, empowered, powerful women during and after treatment. Doing it together is really, really a great vehicle of support to do that.”

Paula Ruska, who was diagnosed with throat cancer when she was 68, experienced severe fatigue and feeling depressed after completing treatment. Then, after a recommendation from a friend, she started going to Power Plate workout classes, which involve exercising while balancing on vibrating platforms, and loved the support from the group environment.

“I feel like I am in better condition than I was before the cancer,” Paula says.

Moving your body and getting active during and after cancer treatment will be a challenge–and it can be incredibly rewarding. You deserve to feel strong, capable, and supported, both in your body and mind. Jadey encourages you to chat with your doctor about how you can get your body moving, what is safe to do, and whether seeking expert help through your cancer center’s exercise oncology program, a physiatrist, or physical therapist would assist you with your goals. Your body is strong, and cancer doesn’t mean you can’t take time to make it even stronger.