I stared at the candle on my coffee table, blinking through tears. The fancy-shmancy candle had sat idly, unlit, for five years with a thick layer of dust collecting on its waxy black surface. I will light my candle today, I thought. I have cancer. I should light it.

The candle had been a birthday present, and cost $38. Googling the cost of gifts was one of my more unattractive qualities, but I could not resist the dopamine hit each time I deducted the price from my credit card balance; as if I had saved that exact amount of money. But even still, I could not bring myself to burn the candle all those years. Who was I to light money on fire?

Now that I was facing my mortality at 35, though, it seemed right to finally luxuriate in $38 worth of fig and oud fragrance. “Come on Sarah, live a little!” said a hospital social worker, encouraging me to stop being so frugal and get my priorities in order. “You have cancer. Light that candle.”

I thought I would come out the other side a better person. If I could only do that, then the unfairness of cancer would be justified.

The radiologist had pawned me off to the social worker just after I bawled to her on the phone for 20 minutes too long. “We found a touch of malignancy in your left breast,” she had said coldly, a tone indicating she was neither my therapist nor my mother. I hung up, cried, and puffed many labored breaths into a brown paper bag. Being told I had cancer days after losing my job felt … excessive. Needless to say, March 2023 was not my month. But when I eventually settled into a kind of stunned silence, I began to wonder if the social worker was right.

After being fed endless depictions of the “wise cancer patient” in movies and TV, it seemed only natural to expect meaningful change. I tried to imagine how cancer might instantly propel me into sainthood, à la Susan Sarandon in Stepmom; how it could shift my values and show me what really mattered. Holding onto an expensive candle wasn’t important; enjoying it burn was. I could finally learn who my true friends were, how I should spend my time, and with whom. I could stop procrastinating on passion projects, and do that open mic, write that essay, paint that portrait! My cancer teacher would make me a sage, doling out advice to others from on high.

Later, I learned I wasn’t the only one hoping for a transformation.

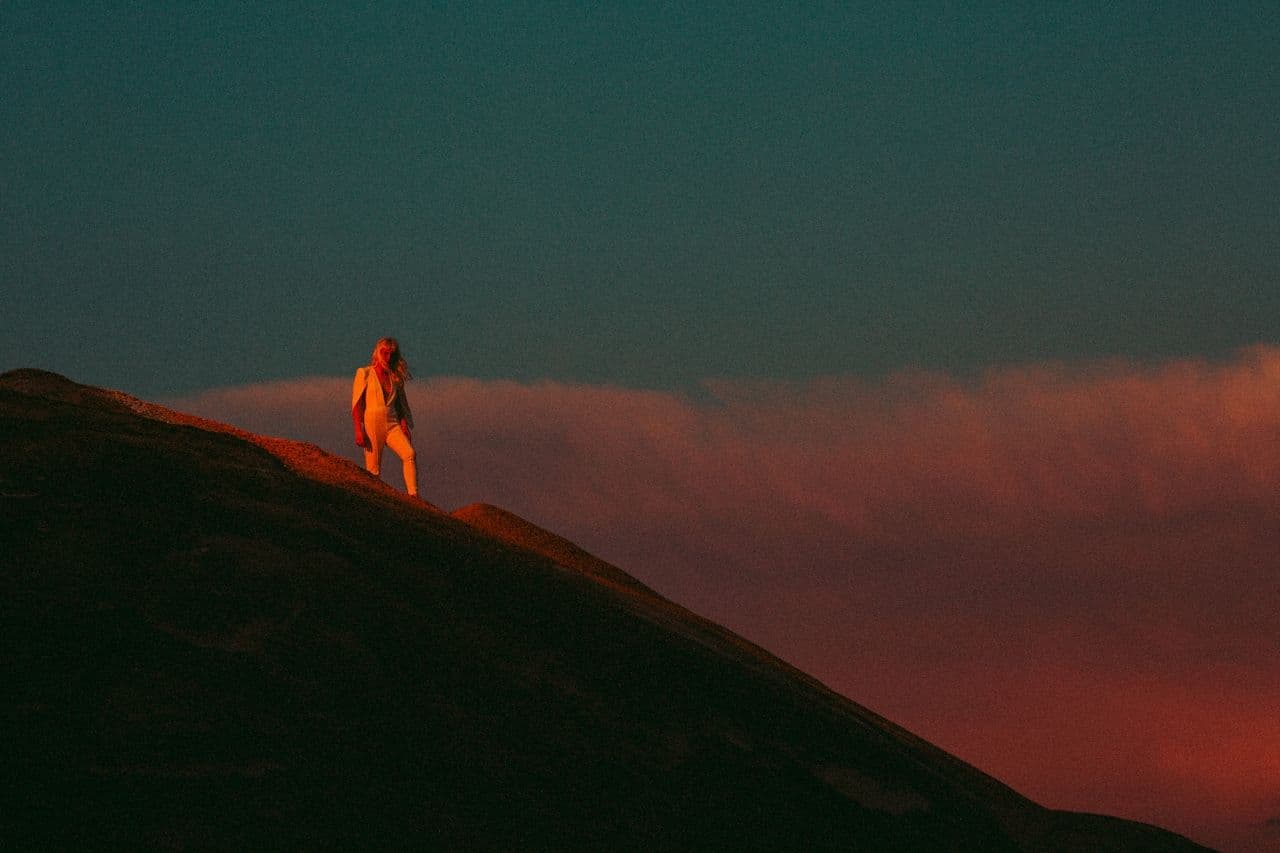

Taken before Sarah went in for her breast surgery (oncoplasty) in Los Angeles

“Obviously no one wants [breast cancer] but I tried to view it as an opportunity to reset my priorities, relationships, vices, and outlook on life,” says Frances, 29. I met Frances briefly this year at an NYC Breasties event, a non-profit for those impacted by breast and gynecological cancers. She told me that before she finished active treatment a year ago, she dreamt of who she would be in her cancer-free, post-chemo life. “I would be eating all of the recommended servings of vegetables each day. [I would be] the healthiest and strongest I have ever been. I would have almost too many deep, drama-free friendships and maybe I would even fall in love.”

Like her, I thought I would come out the other side a better person. If I could only do that, then the unfairness of cancer would be justified. And so, I immediately put my newly aligned values into practice, and two days after being diagnosed, I finally finished an essay and performed it at an open mic that I hosted. I felt completely self-actualized and very powerful.

How unfair that cancer is supposed to be a therapy crash-course that demands I emerge enlightened! I didn’t want to overcome years of financial insecurity to finally light a fancy candle. I wanted to get through the day without having a breakdown.

But the clarity lasted about three days before my earthly realities set in.

Forget the candle, I thought. I have cancer and I lost my job in the same week! How was I to buy groceries, let alone pay rent and medical bills? The very notion that I should start enjoying the finer things in life and transcend my scarcity mindset to live a life of abundance seemed utterly ridiculous. Words like mastectomy, chemo, infertility, radiation, and medically-induced menopause were also entering my orbit, making it clear that this journey was going to be more than “just a simple lumpectomy,” as my mom had previously tried to assure me.

Before I could even begin my proverbial ascent to Mount Olympus, my sister, Sophie, was also diagnosed with breast cancer at 37 years old– her diagnosis came just five weeks after mine.

In the absurdity of now having cancer alongside me, all Sophie could do was hope to “become a stronger, more resilient human being.” When I asked if she believed cancer would change her, she said, “I thought it would give me a greater perspective on what is truly important and therefore I would no longer feel anxious about stupid, mundane things in my life.”

Sarah and her sister in Montreal to see totality in 2023 just after they both finished active treatment.

For me, though, mundanity often took centerstage; the Los Angeles traffic on the way to doctor appointments, the endless hours on hold with insurance, the weeks spent swinging on a hammock in my parents’ front yard between chemo infusions. In fact, there was so much mundanity that I barely had time to process any of the big life lessons I thought I had learned when I was first diagnosed.

Frances believes the forced optimism from her early days of treatment simply was not sustainable. Though she had hoped it would stick, she tells me she “didn't emerge from the chemo fog a brand new, shiny person with a perfect attitude.”

The deeper I got into my own cancer journey, the more I felt that the pressure to find profundity in it was harmful. How unfair that cancer is supposed to be a therapy crash-course that demands I emerge enlightened! I didn’t want to overcome years of financial insecurity to finally light a fancy candle. I wanted to get through the day without having a breakdown.

I began to worry: what if I came out the other side of cancer just the same? But then an even deeper fear started to surface: What if I didn’t?

I began to think that maybe cancer would change me, after all. It would saddle me with medical trauma, rendering me unrelatable to my peers. It would alter my physical appearance making me bald with sallow skin and sunken eyes. My relationship with my sister would hurt as we butted heads on medical decisions, and cancer would limit the ways in which I could enjoy my life: No more casual wine nights with friends as alcohol is linked to recurrence; no more guilt-free burritos since menopause would halt my metabolism, and no more spontaneous hookups because treatment would kill my libido. Chemo would rob me of my choice to become a mother, and menopause would age me, rapidly.

I became profoundly afraid of how cancer might change me profoundly.

A photo of Sarah taken the day after she shaved her head.

Meanwhile, Sophie seemed to be changing for the better. “During treatment, I was able to access a completely zen version of myself and felt deep acceptance for the things I could not control,” she says. “I was walking around with zero anxiety; something I had never experienced in my life.” I was jealous.

My evolution never seemed to come, and in that struggle, I sought out the support of other breast cancer survivors – mothers and aunts of my acquaintances, friends of friends, co-workers, and others. Soon, I had a group of strong women around me, and I couldn’t help but acknowledge my newfound ability to connect and build community. Did cancer teach me that? I wondered.

When I was faced with impossible decisions about my body, I chastised myself for being as indecisive as I’d always been. Shouldn’t cancer have taught me that my life was more important than my hair? I couldn’t seem to get my priorities straight. Sitting in the chemo chair, though, I asked for ice chips and a third warm blanket, and realized I’d learned to advocate for myself in ways I’d never done before. It appeared that, actually, I was changing, but in none of the ways I had expected.

Cancer reshaped Frances in surprising ways as well, and left her just the same in others. “I am still anxious about the same things but new fears and insecurities have moved in. I care a little bit less about trivial things because I am spending most of my time worrying about recurrence or how the tips of my fingers are still numb from Taxol.”

Was cancer changing us too much or not enough? Was it changing us in the “right” ways (i.e. the cancer sage) or the “wrong” ways (i.e. the anxious, confused sick person)?

Sarah with her sister both wearing wigs (though Sarah's sister was wearing hers just for fun; she didn't do chemo).

To add another layer of confusion, some of the positive changes we wished would last didn’t, and some of the negative ones we wished wouldn’t, did. For example, Sophie made it through active treatment, but the new “zen” version of herself did not, and once it was all over, her anxiety returned, full-force.

When it came to Sophie and my relationship, people seemed to want a grand story about how cancer strengthened our bond. But the truth was, it didn’t. Cancer neither made us closer nor drove a wedge between us. Instead, we simply supported each other through our individual journeys as we would for any other situation in our lives. Cancer didn’t change our sisterhood at all.

“There’s a strange sense of grief and disappointment when cancer doesn’t deliver the profound, magical transformation you think it would,” says Sophie, who over time, learned to let go of unrealistic expectations and to see “cancer as a teacher rather than a magic wand.”

“Labels like ‘Thrivors’ and ‘Survivors,’ implicitly suggest that you must emerge as a powerful, new person. While the transformation is real for some, those labels should come with a major caveat that sometimes, you just get to go back to being yourself, flaws and all, and I guess that is some kind of victory in itself.”

Frances also expressed a lack of deep, fundamental change, but told me that these days, she is eating more vegetables, and has made a point to surround herself with “people that inspire me with their curiosity and kindness.”

In the end, it felt as if the ways cancer did and didn’t change me balanced out, and I came out the other side still fundamentally me, which, as my sister said, felt like a victory. Of course there were big life lessons to be gleaned from the experience, though I have yet to really absorb them.

Now, I am almost three years out from my diagnosis, and still have not lit my fancy-shmancy candle. But now, the candle has taken on new meaning and I see it as a symbol of who I was before cancer. I take comfort knowing the candle has remained intact all this time, and that version of myself pre-cancer has not melted away, even a little bit.