Ash Davidson was prepared for a life upheaval after a scheduled surgery in October 2022. He was getting top surgery, something he'd wanted for years. Following his doctor’s advice, he got a mammogram six months beforehand and then an ultrasound: both were clear of anything suspicious. Then during the operation, his surgeon found a cancerous mass. "I thought I was about to enter the best part of my entire life—and eleven days later, I heard the worst news of my entire life,” he says.

Ash faces dual challenges of navigating cancer and navigating the systemic obstacles for trans people in any medical context. Since his cancer diagnosis, he's started work advocating for trans people facing health crises like cancer. He approaches his activism and writing about cancer with kind, understanding, firm grace.

In this conversation, Ash talks to Jadey about how to assess your care team, how to find a queer cancer community, and how to navigate affirming language and administrative errors. He also suggests some concrete ways that healthcare providers can support their trans, queer, and nonbinary patients.

I didn't forget about transition, but everything that was supposed to be trans joy became cancer. And I've got this incredibly gendered cancer, where everything is pink and everything is geared to women. And I thought I was just leaving woman stuff behind—and now I'm thrust back into it.

Q:

I’m starting with a personal, but relevant, question: How’s your health?

A:

Health-wise, related to cancer, there's no easy answers here: about a year ago, I was infected with West Nile virus.

What!?

Yeah, it's wild. There’s a running joke with some friends that I'm really rare. It’s really rare to find cancer during top surgery and now I have West Nile. The weird part of that is a lot of the symptoms of West Nile mimic what might look like a cancer recurrence–and so I've seen like a thousand different specialists and had a thousand different tests. The good news is all those tests are coming back negative in the right way. And so it does look like it is most likely just West Nile and not a cancer recurrence.

Q:

I thought a potentially good way to ask for some broad advice, for other trans people with cancer, would be to ask what advice you’d give yourself at the time of your diagnosis?

A:

I suffered from a lot of mental health issues after my diagnosis, related to isolation. I felt too overwhelmed to even track down resources specific to trans or queer people—but I would really tell myself: Suck it up. Do whatever you can to get the energy to find some of these resources for yourself, because no one's going to hand them to you, but they're really going to help.

If you have breast cancer, and you go to your first appointment, you're probably going to leave with a big binder. It’s going to have all sorts of information: financial resources, legal resources, support groups, what cream to use for radiation. Of all of these things in that binder, it didn't have a single queer related resource in it.

The isolation starts right away. People said: ‘You should go to a support group’ But I was like, Which one? Should I go to the one with all the ladies? Should I go to the one with two dudes? Neither of those really fit. These are the preconceived notions I have, but I had concerns if I went to a women's support group, that they're going to think I'm invading their space, because this should be a space for women to talk about women's things. I’m going to show up and they're going to be uncomfortable.

I started just reaching out to organizations on Instagram. I reached out to Queering Cancer and The Cancer Network. They've got support groups and research. They do a lot of advocacy work, a lot of education and training. A peer of mine that I met along the way just started a peer-to-peer resource group and support group called Cancer Queers in Portland.

This the onus should not be on the patient to do this work, but unfortunately it's the way it is.

Q:

How do you navigate talking to your providers about language to use? It can be a battle, if you have a new team every twelve hours for an overnight stay in the hospital. How do you think about the energy to educate your team?

A:

If using the word breast makes someone uncomfortable, then using the term chest cancer should be used as a more inclusive way to refer to the clinical term "breast cancer". Personally, for me, I'm comfortable with calling it breast cancer and chest cancer. I also know that there's a difference: there is cancer of your chest wall versus cancer of your breast tissue. Those are two different types of cancers, and so there is a distinction there. But through some of the consultancy work I've done, I’ve heard from trans chest cancer patients that the word “breast” to describe their cancer sets off dysphoria for them. So when you’re in conversation, it’s important to be receptive; some terms could make people uncomfortable.

In terms of navigating my own body with my care team, I was so early in transition when I got diagnosed. I've wanted top surgery for as long as I can remember, in the sense of not wanting to have the chest that I had. But I never even really realized that top surgery was an option for me. Once I kind of realized it was something that I really could pursue, it all happened pretty fast, like within a year. But a quick timeline check: I started low-dose testosterone therapy in June of 2022. In the first week of October, I had top surgery. Then the cancer thing piles on top of that—and it was so shocking. I didn't forget about transition, but everything that was supposed to be trans joy became cancer. And I've got this incredibly gendered cancer, where everything is pink and everything is geared to women. And I thought I was just leaving woman stuff behind—and now I'm thrust back into it.

I didn't even think about if I needed them to or wanted them to talk about my body in a different way. I felt a lot of things, but I just didn't quite fully know how to advocate for those things. Focusing on my transition fell behind me, and everything was focused on cancer. So when I was in these rooms with doctors, I was very much on autopilot. I just did what they told me to do. I showed up where they told me to show up. I didn't ask a lot of questions.

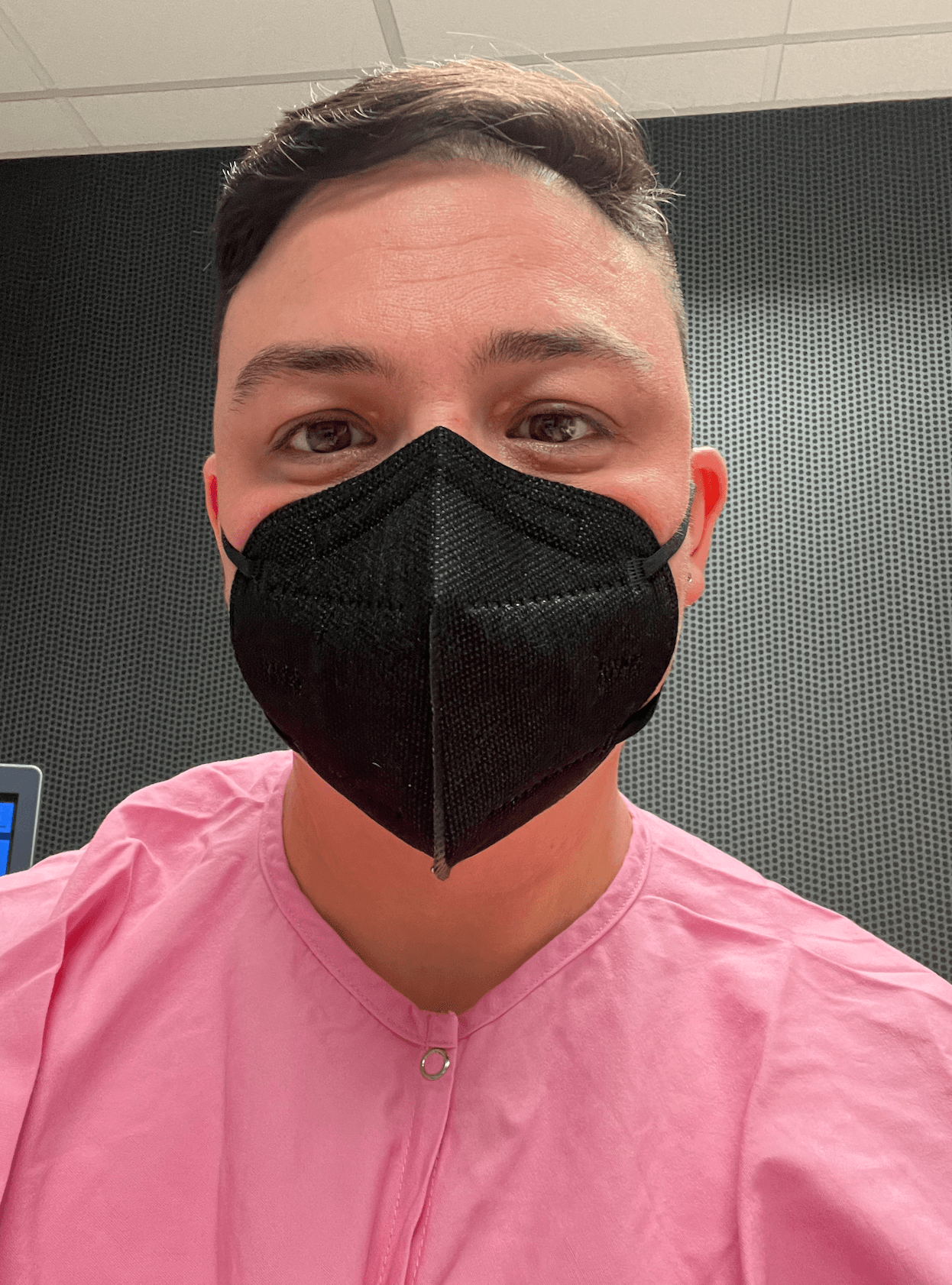

I was also in a pink gown at that very first appointment. There were a lot of things where I was, very quickly, like, I'm in the wrong place.

Everybody has something to say about trans people right now, everyone is talking about us, and no one listens to us. It is getting harder and harder and harder for trans people to use their voices. We’re not a monolith. We're not all the same person with the same needs and the same concerns. We're all different people, and all have unique things going on in our lives.

Ash Davidson in the provided pink gown.

Q:

What advice would you give to trans people about assessing their medical team? Are there questions you should ask your oncologist, to help give a sense of whether they will respect and care for you?

A:

There are some places where you can get information on trans- and queer-friendly providers; the Cancer Network has a welcoming provider directory. I also suggest going to other queer providers in your area, even if they’re not cancer providers. You can check with a queer health clinic about vetting they’ve done. This the onus should not be on the patient to do this work, but unfortunately it's the way it is.

If your care team can't and won't see you as a person and treat you with dignity and respect, then you will likely need to find another team--but I know this is nearly impossible for people in rural areas to do. And it can also be nearly impossible in more urban areas depending on where in the country you are. So, if you are struggling with your care team and can't just simply get a new one, then turning to those national resources for help on where to go is a good next step. And there are programs and orgs that may be able to help find new care or advise you on what to do.

So if you hit a dead end with trying to find referrals through other queer health networks, if you realize you are in the hands of somebody who does not see you, that's when I would reach out to these more national networks. They can help. Is it a financial thing? What are all the different barriers that you're facing? There are a lot of queer networks that will help with those things. If you need transportation to get to a bigger city, they'll help fund that transportation. There's access out there.

There's an unfortunate amount of trial and error that's involved with finding a provider—and I hate to say that, because it's not very helpful. But I don't really sugarcoat this kind of stuff. There are just parts of this process that are just really unpleasant.

Q:

Do you have advice or strategies about communicating with healthcare providers about pronouns or dealing with administrative errors?

A:

My approach is going to be different from other people's approach; mine isn’t to condemn and finger-wag, but to meet people where they are, or at least be kind in my responses.

I'm in Austin, Texas. Austin's progressive, Texas is not exactly. For every one of my chemo appointments, when I would get called back to do my blood work, and they would continuously call me back as Miss Davidson, and I look like this. It got to a point where it first was annoying, and then it was scary, right? Because I'm in a room of 50, 60 people. And I know most of the people in that room are just looking at their phones and they're not paying any attention to me, but I felt like everyone would watch me walk to go get my blood work. After your blood work, then you go to chemo, and then you walk out to your car. I was like, Well, what if somebody were following me to my car and wanted to say something or do something to me?

You could tell they were super well-meaning. I was always like, ‘Hey, can you guys please update that?’ And I said it really nicely. I would see them in the lab, typing something into the computer, so they were making notes in my chart; it was a system thing, it just didn’t update. Finally, two appointments ago, so that’s exactly three years later from when I was diagnosed, was the very first time I got blood work done and they didn't call me Miss Davidson.

Maybe it would have been more effective for me to raise hell, and be like, This is horrible! I could be put in danger. But it’s just not my way.

Good experiences happen every single day too, and I've had really good experiences. It’s important to me to highlight them, because I want people to get preventative care. I don’t want to contribute to statistics that say trans people show up sicker and later and their prognoses are worse.

Q:

What can health care providers do to make the experience safer, more welcoming, or kinder for people who are trans, or nonbinary, or queer?

A:

One of my favorite ways is super simple: when you introduce yourself to a patient, use your pronouns. Because I know if you're using pronouns with me before I even use mine, you're going to respect mine. It doesn't require you to plaster queer flags all over your office. It's just a little verbal cue. I think it's powerful, but small.

The other thing to really be aware of is that trans patients are facing an incredible amount of other things going on in their lives. Even as a white trans person who has some level of passing privilege, I’m worried if I can stay in Texas. Should I leave the country? I'm worried about my personal safety, just day-to-day.

My medical oncologist, for example, she's busy. She doesn't have time to do this. She calls me once a week because I've been having this weird stuff with West Nile. And I've had a really hard time with mental health and my surgical oncologist physician assistant set up once a week meetings with me, in person, just to check in and how I was doing mentally, because I was struggling so much. I know providers are busy, but when you do stuff like that, it makes a massive difference. I probably would have been okay had that PA not set up those meetings with me, but I was more okay because she set up those meetings.

That’s incredible.

For every horror story I have heard from people about health care, especially as trans people, it's important to me to tell the good stories. There are a lot of amazing, incredible cancer providers, researchers, healthcare workers who try really, really, really hard. Even those who don’t get it right all the time, they want to.

Because if we don't start sharing positive stories about health care, we exacerbate the problems that we all face, which is the medical mistrust. People then won't go get preventative care because they’re terrified of how they’re going to be treated. I don't want to discount any of those experiences, because they're real, and they happen every single day. But good experiences happen every single day too, and I've had really good experiences. It’s important to me to highlight them, because I want people to get preventative care. I don’t want to contribute to statistics that say trans people show up sicker and later and their prognoses are worse. So one of the ways that I feel like I have a place to combat that is to share some of the good things that have happened, too.

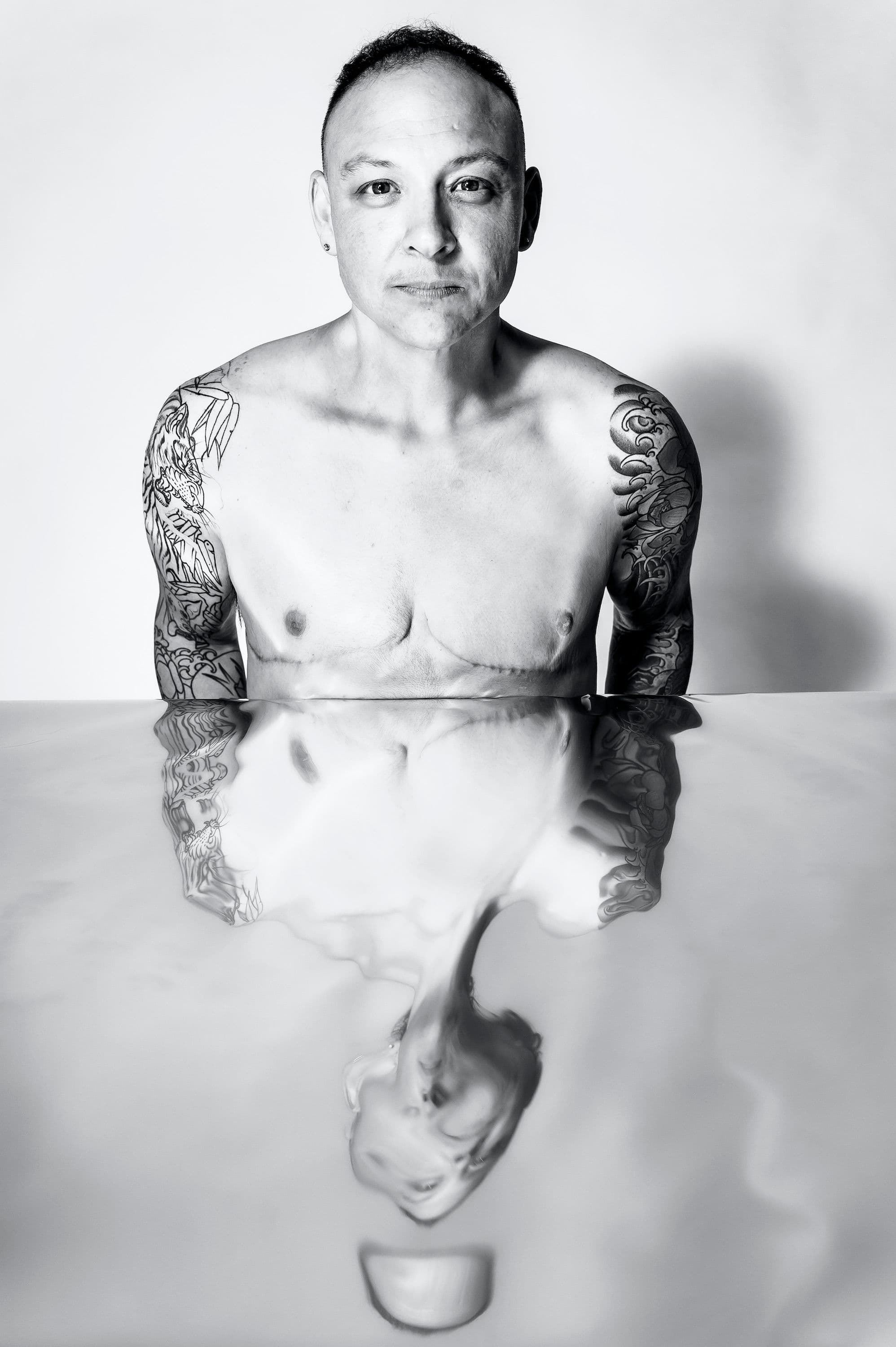

Ash Davidson, photograph by Ann Alva Wieding.