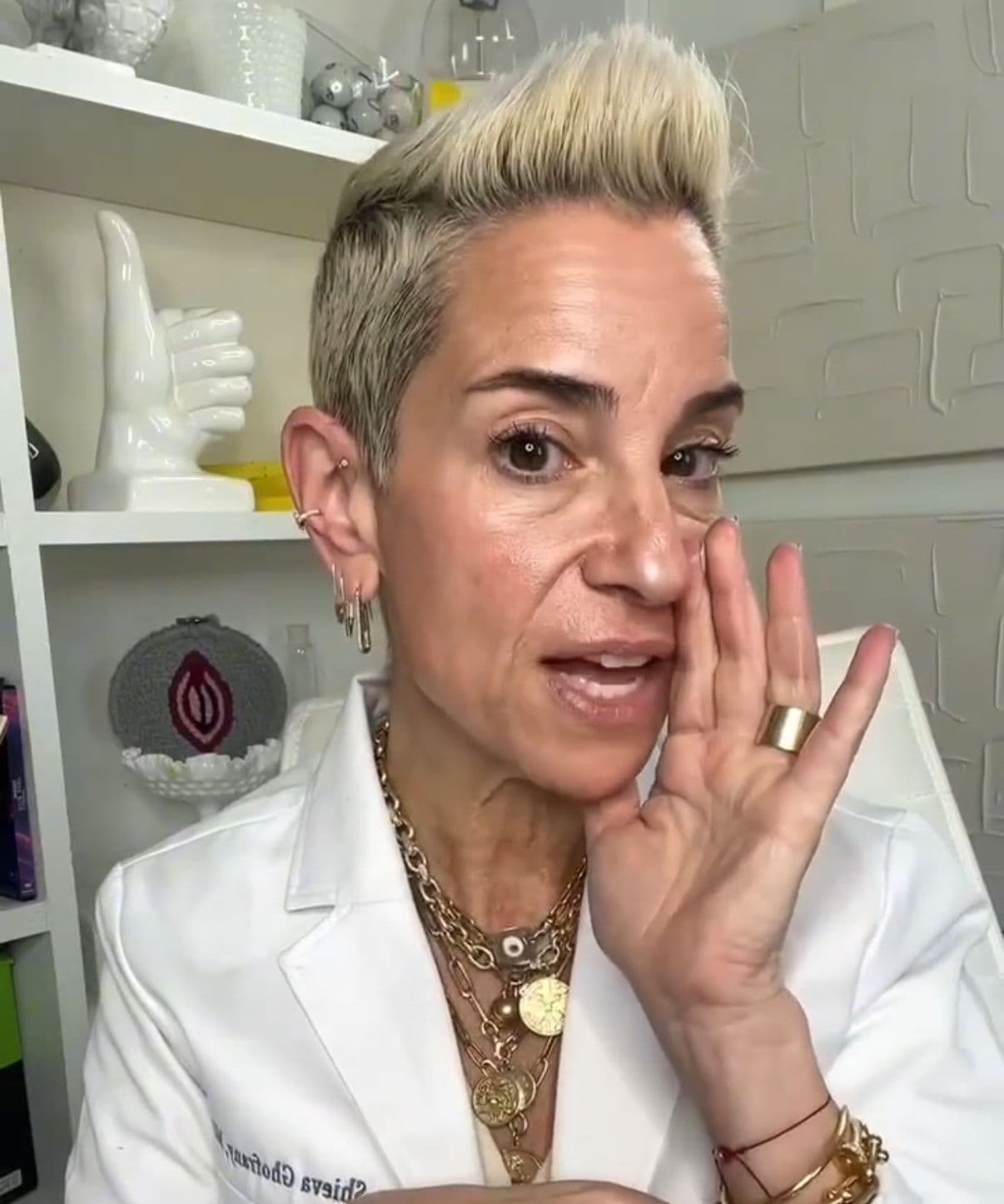

Dr. Shieva Ghofrany

Dr. Shieva Ghofrany is an OB-GYN in Connecticut with Coastal Obstetrics and Gynecology and the co-founder of the women’s health platform Tribe Called V, which focuses on education about fertility, pregnancy and postpartum, and other gynecological health topics.

Over the past decades, the professional and personal life of Dr. Shieva Ghofrany unfolded at the heightened intersection of medicine and advocacy for women's health. Dr. Ghofrany is an OB-GYN in Connecticut and a mother of three who has navigated complicated pregnancies, miscarriages, endometriosis, and ovarian cancer. What distinguishes Dr. Ghofrany is not just the clarity and empathy of her professional wisdom, but her personal experience that informs this wisdom as well.

Dr. Ghofrany works with a private practice, Coastal Obstetrics and Gynecology, and co-founded the women’s health platform Tribe Called V, where she focuses on education about fertility, pregnancy and postpartum, and other gynecological health topics. She actively encourages women to replace fear with understanding and to approach their health with proactive curiosity not paranoia.

Below, Dr. Ghofrany talks to Jadey about rebranding cancer, the importance of foregrounding conversations about sex, and how the best realism comes with some optimism.

Q:

To start, would you tell us about your experience with cancer?

A:

I have been an OB-GYN now for 26 years; I was diagnosed nine years ago, when I was 46-years-old, so at the time, I’d been a doctor for 17 years.

I had a history of endometriosis, so I'd had a lot of painful periods throughout my life. They dissipated because of pregnancies and miscarriages, so between the age of 40 to 46 my period really had not been painful—and then it was very, very painful for a couple of months. As an OB-GYN, I said appropriately to myself, ‘Okay, my period is painful. It's probably my endometriosis, but I should get it checked out, which is what I would tell my patients.’ And checking it out would mean a pelvic ultrasound.

When I finally did, it showed an abnormal cyst in my ovary, which again could be endometriosis. But my ultrasound tech said to me, ‘I know what you would do: you would tell your patients to go get an MRI. So why don't you order yourself an MRI?’ I said I’d do it to put my money where my mouth is. It turned out it was a very, very, very early cancer, something called a borderline cancer. I had surgery; and it was not a borderline ovarian cancer, it was a stage two ovarian cancer from my endometriosis.

Q:

You’re very skilled, in your public advocacy about cancer, about encouraging screenings and tests–while not encouraging intense anxiety about tests and screening. Tell me about this.

A:

In a broad sense, I really feel like I want to debunk this smear campaign about cancer. And I really try to discourage people from using the word ‘fear.’ I always say it's normal to be nervous. Nerves are normal. But don't be scared, because it really leads to a lot of downstream effects that are not going to help us with cancer. That's kind of the broad PSA that I try to get into people's minds. I want to teach women to understand their bodies, to know their bodies and to not ignore things, but also to not freak out about things.

Something like one in two women, or approximately 40% of women, will get cancer in their lifetime—which is a huge number. And we could digest that number and say, ‘That's so scary.’ Or we could say, ‘Oh, wait, it's actually so common.’ The vast majority of people who are going to be diagnosed with cancer are going to be diagnosed with an early stage of something. Through a little bit of luck and a little bit of strategy, we're going to get better at detecting cancer early and the vast majority of people are going to survive.

‘You can complain. In fact, I want you to complain, while also recognizing there are probably some good things within the shitty part, so let's look at both.’

Q:

How did you maintain this, to me, very enviable mental state—where you’re realistic, you’re confident and informed, and you’re optimistic.

A:

I think grasping the good parts really did help me feel better about the prospects. I always say bodies are just vessels that are unfortunately prone to damage, just like a car. We are lucky enough to inhabit this vessel. My vessel can break just like anyone else's, and if I get through life without it having broken, then I was merely lucky.

I needed to train myself to find the beauty within the suck when things are the worst. Like the moment I was diagnosed. I thought: I had already gone through training through my miscarriages and my son’s stroke and all that. I get diagnosed, it sucks. There's no two ways about it. You have ovarian cancer. You didn't expect it. You're 46. But the beauty was, Okay, but I am a doctor, so I can traverse this probably better than other people. I'm lucky that I have family and financial resources. I'm in a hospital where I trust the people. I can digest the information.

The minute someone tries to throw out some pithy saying like ‘the glass is half full’ or ‘look at the bright side,’ I rail against that. Because even though that sentiment is actually exactly what I'm saying. But those little Hallmark sayings have not only lost their value, they border on toxic positivity, which I would never want.

The flip side of that is not, to me, to only look at the negative. It is to say, ‘let's look at the positive, but we have to, all at once, recognize that we need to sit with our sadness, discomfort, pain, anger, anxiety, all of it, while also recognizing the beauty within the suck.’

If I say to someone ‘How are you doing?’ and they say, ‘Oh, I don't know, I can't complain,’ I always joke, ‘No, you can complain. In fact, I want you to complain, while also recognizing there are probably some good things within the shitty part, so let's look at both.’

I don't know why people don't try to choose optimism a little bit more. It’s just valuable and helps you feel better. And I think that probably the reason they don't is because they don't recognize that you can do both. They probably think that optimism negates their right to be anxious, angry, whatever it is. I think sitting with both is so much more valuable.

And I really try to discourage people from using the word ‘fear.’ I always say it's normal to be nervous. Nerves are normal. But don't be scared, because it really leads to a lot of downstream effects that are not going to help us with cancer.

Q:

What are the very most important things you want people to know about cancer and their health?

A:

I think these three things are the best concrete things to know.

I want women and people with ovaries to know that they get screened for breast cancer with a mammogram, colon cancer with a colonoscopy, cervical cancer with a pap smear. They might get screened with skin cancer. And they might get screened for lung cancer if they have a history of smoking— but otherwise it's breast, colon, cervical, no other cancers are screened for. That is shocking to people when I say that, because they assume they're getting screened for a lot of cancers. With regard to ovarian cancer, in particular, most women do not realize that there's no screening test for ovarian cancer. They often come out of doctor's offices thinking, ‘I had my pap smear. It was normal, therefore I'm okay.’

For ovarian cancer, there's not a screening test, but what I do tell patients is to be very vigilant about symptoms like bloating and pain and pressure. These symptoms, if they last for two weeks, should prompt them to see their clinician and ask for a pelvic ultrasound or other testing.

And I want every person to know their family history. They should know their parents’, siblings’, grandparents’, cousins’, anyone that they are first or second degree related to. They should know all the cancers—and they should never accept someone saying, ‘Well, that was a cancer that wasn't the genetic kind’ or ‘That was prostate cancer and you’re a woman.’ We know that prostate cancer can increase the risk of other cancers. We know that there is no non-genetic kind of cancer, meaning there are cancers that don't have a genetic component, but we wouldn't know that unless we continue to test. We need to keep doing genetic testing as we learn about new genes as science evolves.

And then the last thing is: if we just got out the word about vaginal estrogen to more women, who have cancer or not, it would actually improve lives so much.* Vaginal estrogen is such a valuable, useful tool that is relatively inexpensive. It’s very safe for almost every person with a vagina and vulva, apart from a very narrow group of people with certain types of cancers. Otherwise, women with breast cancer, women with ovarian cancer, with colon cancer, even the ones that are estrogen receptor positive, really can use vaginal estrogen safely. That alone would actually improve sexuality, decrease urinary tract infections, make their vagina and vulva much more comfortable. Going through chemotherapy and radiation can be so painful in that area. If we could get the word out about it, we would actually vastly improve outcomes.

[*As Dr. Ghofrany says, this is likely safe; but this is something to check with your medical care team about, of course.]

Q:

Yes, let’s talk about sex and sexuality and cancer. I’m so glad you brought it up first, and I think that’s a great thing you’re doing as a doctor. First, I’ll ask: why do you think that doctors don’t bring it up more?

A:

I think it's a couple of reasons. One is, let's face it: we are still in a Puritan, weird place where we hyper-sexualize everything, but we actually don't really talk about sex and sexuality.

Two is our systems aren’t set up easily to address sex. With fertility, the medical and surgical oncologists can say to you that you need to see the fertility specialist, here's the referral. Now, imagine a world where the oncologist could also say, ‘I’m going to send you to the fertility specialist, then you're going to be sent to the sexual health clinic. Here's the referral for a sexual health clinic, and they’re going to have a mental health therapist, a pelvic floor physical therapist, and maybe a nurse navigator, and people who understand what hormones you can use.’ If they could just make that referral, that would be great. But that requires some resources and certain insurance. I will say some oncologists are really good about doing this, but it means you still have to coordinate.

Plus, let's face, women are reduced to how much value we bring with regard to having babies.

What I say to patients when they get kind of angry that an oncologist didn't talk to them about something or bring something up, is that the oncologist has so much to do. They have so many studies to review. They have so much on their plate in order to make sure that they are essentially just getting rid of your cancer– that it almost seems like an unfair burden to also ask them to be the ones in charge of your mental health, your sexual health. Those are all things you deserve to know about, but it's unfair to ask this of the oncologist and it's going to be a losing prospect for the doctor and patient if we put that burden on the medical oncologist. So we really need care teams. But many hospitals just either don't have the money for it, or don't put the money towards it.

Q:

What are the major things you’d like people with cancer to know about sex?

A:

There are so many levels. People who are having abdominal or pelvic surgery—whether it's ovarian cancer, uterine cancer, cervical cancer, colon cancer—regardless of whether they're having any interruption of their actual hormone status, there's so much that can come up with just that alone. How do you feel psychologically after you have a lot of scars? Do you have any pain left over from your surgery? Do you have scar tissue inside that might make it harder to have sex?

Plus, when you're going through chemotherapy, you might be nauseated. Then add to it the layer of women who go through surgical menopause once they lose their ovaries. For me, I was 46: I wasn't considered to be in early menopause, but I still went through surgical menopause because my ovaries were removed before I'd stopped getting my period. Your hormones overnight stop working.

So besides the fact you have hot flashes and night sweats and anxiety, your vulva and your vagina and your urethra and your bladder all suffer the loss of estrogen. That really leads to absolute painful sex—if you even feel like having sex, because your libido probably has already taken a big dive because of your lack of hormones, because of your anxiety and stress.

Q:

And what are the solutions you recommend, that women should be asking about here?

A:

Certain women can take hormones. Almost all can use vaginal estrogen, which alone would really improve sexuality. Do they need help with pelvic or physical therapy? Have they already been in relationships where sex was already a problem, and this just made it worse? Was their partner even supportive of them during their entire cancer journey? There need to be multiple modalities—and we really fail in that regard, with regard to sexuality.

I have heard some devastating stories of young women who had no discussion, no help, and they left, essentially, to feel like they couldn’t even think about sexuality. And that shouldn't happen to anybody, but it does.

Unfortunately, very few cancer centers have a really good survivorship program that addresses sexuality. I would love the surgical and medical oncologists to talk about this, it's just a lot for them to have to take on. So I do place a little bit of blame that they don't talk about it more, but I also don't want to blame them, because they're literally responsible for keeping us alive and learning all the new regimens and reading all the data and studies. So to take on this really big topic, which requires nuance: it takes a lot to be able to educate women on it really preemptively before they go through treatment, so they know what to expect.

Q:

I know that in addition to surgery and chemo, you also pursued acupuncture and did transcendental meditation as complementary treatments. I would love to hear both about your individual experience and then also hear how you think about complementary practices as a doctor.

A:

I will say, first, as a doctor in the Western medical field, American healthcare does not do a great job of integrating because our healthcare system is broken, and it's still largely for profit. I don't foresee that changing. Sadly, because of that, the whole notion of integrative health has fallen on the consumer, who is the patient. The reason I say consumer is that it becomes a largely consumerist endeavor. People who are very resourced, either from education or time or money, have access to complementary and alternative ways of helping themselves. People who are not resourced rarely get that opportunity. And even the people who are resourced financially or from an education perspective, often get taken advantage of because they're being sold a lot of complementary alternatives that either try to negate their actual health care—or ones that do try to complement it, but at great cost and without a lot of data behind it.

There are some specific examples where there is good data. We know that acupuncture really has been shown to help.

I always joke like I'm going to take my toxic chemotherapy. It’s toxic to the things I want it to be toxic towards, like my cancer. It's unfortunately going to cause some side effects—and then I'm going to try to mitigate those side effects and risks by doing these complementary alternative treatments, like meditation so that I could sleep better and feel less anxious.

I found it to be really helpful, especially acupuncture. I honestly started doing acupuncture mostly because one of my best friends was an integrative physician. I really looked at it more as this is just an hour to relax. I thought, I don't even know if this is going to do anything. And the one time I had a chemo session where I didn't do acupuncture, I felt so much measurably worse. It was a profound experience, because it really meant that it could work. It couldn't have been placebo in my mind, because I went into it thinking, This isn't going to help me at all.

And I recommend support groups, which aren't touted as complementary and alternative treatment, but they really are, in so many ways, the most valuable and important thing. Because no matter how wonderful your family and friends are, if they have not been through it, there are just certain things they're never going to get. Getting to a support group can really heal you psychologically and just help you. They'll give you tips and tricks. I learned things from other patients that my oncologist wouldn't have necessarily taught me about how to get through chemotherapy. And there's no replacing the mental health of being able to communicate with other people who've been through it, especially when they're on the other side, and they give you hope. It’s so valuable.